Large constrictor

PRE-OWNERSHIP ASSESSMENT and GUIDANCE

This comprehensive guide aims to provide prospective owners and businesses with essential information regarding the responsible ownership of large constrictor species. Our commitment to promoting responsible reptile ownership is reflected in the thorough education and preparation of potential owners.

This large species policy has been created to align REPTA and member businesses with government expectations for companion animal sectors to demonstrate a means of self regulation. Through self-regulation REPTA can show that the reptile industry is proactively addressing the potential issues, thereby limiting the undue influence of radical animal-rights campaigns.

What is a large constrictor?

This guide references large constrictors from the Python or Boa families of any species where either sex may commonly surpass 400cm (12ft) in length – specifically:

- Reticulated Python (Malayopython reticulatus)

- Indian Rock Python (Python molorus)

- Burmese python (Python bivittatus bivittatus)

- African Rock Python (Python sebae)

- Amethystine Python (Simalia amethistina)

- Australian Scrub Python (Simalia kinghorni)

- Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus)

Rationale for REPTA’s guidance

There has been a proliferation of breeding large constrictors within the UK. Because of the potential future financial, spatial and energy consumption factors involved in large constrictor management REPTA considers the thorough education and preparation of potential owners to be of great importance as part of our commitment to responsible reptile ownership.

REPTA understands that reptile owners never purchase an animal with the intention to relinquish ownership of their companion animals, but the species within scope here have potentially demanding requirements which are at risk of being underestimated by new owners. However, the rehoming network for reptiles is underdeveloped, and the lack of support from national animal welfare charities means that rehoming options for large constrictors is severely limited.

Large constrictors have also come under increasing scrutiny because of a few high profile large constrictor escapes and there is pressure from animal rights groups for such species to be included on the Dangerous Wild Animals Act (DWAA). REPTA considers this to be disproportionate. The DWAA was conceived to protect members of the general public from maiming and death. In the last 100 years, there have been no public deaths from a non.native snake species. At the time of the Modification Order (2007) to the DWAA appendices, a detailed assessment was undertaken into the possible listing of the large constrictor snakes and DEFRA’s conclusion was that such a listing would be neither justified nor proportionate.

REPTA would therefore encourage all responsible companion-animal selling businesses to exercise a thorough pre-ownership assessment. Such an assessment will flag issues regarding potential future spatial requirements and include considerations for energy consumption.

Large constrictor sales records

Ownership of any companion animal is a considerable commitment and the potential owner should be prepared to thoroughly research a potential new species. Companion animal selling businesses should also take seriously their responsibility to provide prepared and competent homes for any animal leaving their care.

On the next page you will find the ‘Large constrictor pre-ownership assessment form’. Contained within it is a checklist of advice to be given to potential owners, along with permission from the potential owner for the assessment to be sent to REPTA. These records will be held solely to help assess large constrictor sales across the UK. The records will not be used for promotional or marketing purposes. No private information will be disclosed. Any reference in future output from REPTA will be anonymised.

REPTA has included supporting information for specialist companion animal selling businesses to refer to while completing the assessment process. Should businesses selling large constrictors require further clarity regarding the assessment process or the supporting information they can contact REPTA at any time.

large constrictor management

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

1.0 Spatial considerations

Spatial considerations will be a primary focus when considering large constrictor management. Most will purchase their animal when neonate or juvenile in size, when their spatial requirements are much like any other reptile and spatial provision is not an issue. As a large species grows, so does its spatial requirement.

To be able to formulate guidance regarding spatial requirements of giant constrictors, REPTA has used a document prepared by the Federation of British Herpetologists:

FBH Code of Practice for recommended minimum enclosures sizes for reptiles

A copy of this document can be found at www.thefbh.org.

Because the code of practice was ratified by multiple stakeholder organisations including:

- BZVS – British Veterinary Zoological Society • CASC – Companion Animal Sector Council

- BSAVA – British Small Animal Veterinary Society As well as a raft of regional and national reptile-owner societies and groups.

1.1 Enclosure sizes

The FBH Code of Practice uses the snake’s total body length to recommend enclosure standards for all snake species.

- Vivarium length: x0.9 total body length

- Vivarium depth: x0.45 total body length

- Vivarium height: x0.3 total body length

For example, a snake with a total adult body length of 400cm would require a vivarium with recommended dimensions of 360cm x 180cm x 120cm (length x depth x height).

A table illustrating total adult body length and the recommended enclosure dimensions is included on the pre- ownership assessment form and companion animal selling businesses should highlight or circle the assumed appropriate enclosure size for the species being purchased.

1.2 How this relates to the family home

The information contained in the supporting information section pertains only to adult large constrictors. Using the previous example of an adult snake of 400cm total body length will mean the recommended adult enclosure size is 360cm in length (12ft) and 180cm in depth (6ft). This is a considerable amount of floor space.

Due consideration must be given to placement within the home. If purchasing a baby or juvenile snake, due care must be taken to ensure an enclosure of such proportions can be accommodated.

1.3 Space availability long term

Consideration of the future and changes that may take place in the family home is paramount.

- Is your current employment secure?

- Is there any chance that you may have to downsize or modify your living arrangements?

- Is your family still growing and the space allotted for the adult snake could potentially be needed for the arrival of new family members?

- If there is the potential for such an occurrence is there available space outside for an ex-situ enclosure within a shed or summerhouse?

If there is reasonable potential for such situations to arise and there is not the availability of ex-situ space, a potential owner should consider if they can provide for the long-term management of a large constrictor.

1.4 Custom enclosure construction

If an enclosure is to be constructed within the home for an adult large constrictor, due consideration must be given as to how this is to be achieved.

Custom commercial vivarium building companies generally only produce enclosures with maximum dimensions of 244cm x 120cm x 120cm. Commercially available boards commonly used in the construction of vivaria (including melamine or Conti-Plas™, plywood and OSB) generally have maximum dimensions of 244cm x 120cm.

The enclosure required for large constrictor species will be considerably larger than this. Does the potential owner have the required skills to construct a suitable enclosure or the resources to outsource this to a skilled tradesman? Care must be taken to ensure joints between boards are sealed correctly to maintain security of the enclosure and to limit soiling of the household, including water ingress to floorboards and house structures.

1.5 Ex-situ management

Ex-situ housing arrangements for adult large constrictors is worthy of consideration as it will not impinge on available space within the family home. There are two types of ex-situ accommodation for large constrictors. This will often be an outbuilding or garage of a permanent structure that would mean foregoing using such outbuildings for storage, or car parking. Is the potential owner willing to make such a sacrifice?

Another option would be to construct a non-permanent structure such as a shed or summerhouse to house the large constrictor. There are many solutions on the market which could be used for such a project, but they could come at great expense. These types of building are un-insulated and will require considerable work to make them energy efficient.

1.6 Power supply

Ex-situ enclosures without a pre-existing ring main will need to have power fed to it. Given the volume of the enclosure, the power required to adequately heat it could be considerable. This may require a separate ring main to be installed with its own breaker on the fuse box to avoid tripping and overloading an existing ring main. This could include digging a gully through gardens or flower beds to achieve this.

1.7 Emergency power-outage plans

Of particular pertinence in winter, what happens if there is a power outage? There may need to be an alarm on the circuit to alert the potential owner of power supply problems. What contingencies are there for temporary housing in such a situation?

1.8 Security of enclosures

Large constrictors are powerful animals and can create considerable force with which to test doors and vents. Care must be taken, particularly with ex-situ enclosures, to ensure access points and ventilation are escape proof and cannot be pushed open. Sliding glass or access doors should remain locked at all times to prevent accidental escape.

1.9 Safely entering the enclosure

Assessment of the large constrictors position prior to entry is essential. In traditional vivarium this is not a problem because sliding glass doors serve as both a viewing panel and an access route. In ex-situ or whole room enclosure solutions the traditional wooden panel door should be replaced with an uPVC window door such as used in conservatories.

1.10 Water

Large constrictors will require large water containers as some species will bathe if given the opportunity. Given the volume of water that may be required, a plan must be in place to efficiently refresh the water when it becomes soiled. This may involve plumbing in such a water feature, if only to drain it away. Alternatively an external canister filter could be used to circulate and filter the water. All pipe work and any such filters should be protected from exploration by the large constrictor. The use of hosepipes may be more appropriate when it comes to refilling the water container, rather than potentially walking through the house with multiple buckets of clean (or soiled) water.

1.11 Enrichment and climbing

Large constrictors have all the same needs as other companion snake species. Enclosures regardless of size should provide hiding opportunities, foliage for cover and exploration, as well as climbing apparatus. Any such equipment must be robust enough to support heavy-bodied large constrictors.

1.12 Substrates

As a continuation of enrichment, thought must be given to the volume of substrate required to adequately fill an enclosure. This will need to be changed regularly as large constrictors produce prodigious amounts of urates and faecal material. Therefore the floor should ideally be waterproof to prevent seepage and bad smells becoming a feature.

2.0 Energy consumption

Potential large-constrictor owners must appreciate the energy consumption implications of enclosures. All large constrictors hail from tropical or sub-tropical regions and have a relatively gentle thermal gradient. Regardless of the length and depth of an enclosure, heat will need to be provided even at the cool end of the closure.

Although there is nuance, the usual thermal gradient for large constrictors is a basking area of 31–34 Celsius and a cool end of 24–26 Celsius. The greater the enclosure’s volume, the greater the energy required to sufficiently heat it.

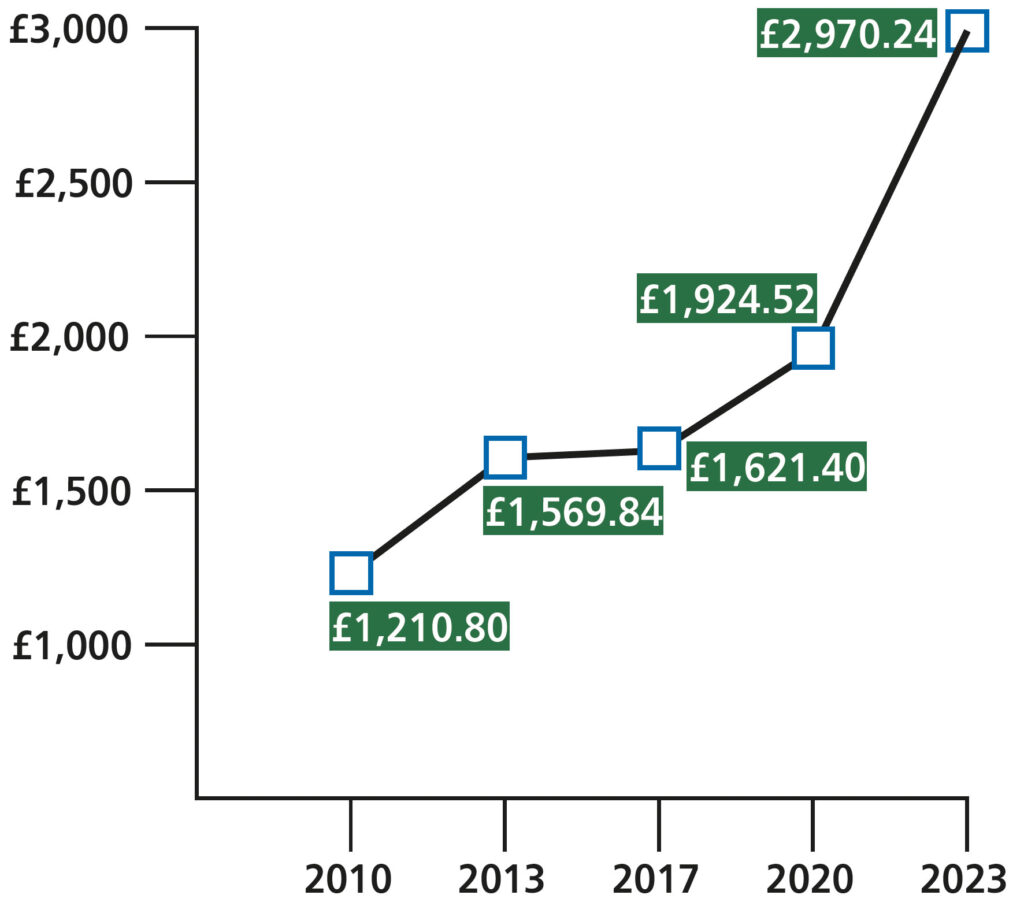

Below is a case study of prices based on domestic energy pricing from 2010–2023 using 250W per hour over a 24-hour period and 1000W (1kWh) over the same period. Prices shown are per year (annum).

180cm 6ft) vivarium

using 250W per hour

| YEAR | ENERGY PRICE | COST |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 13.8p/ kWh | £302.70 |

| 2013 | 17.9p/ kWh | £392.46 |

| 2017 | 18.5p/ kWh | £405.35 |

| 2020 | 22.0p/ kWh | £481.13 |

| 2023 | 34.0p/ kWh | £742.56 |

300cm (10ft) vivarium

using 1000W per hour

| YEAR | ENERGY PRICE | COST |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 13.8p/ kWh | £1,210.80 |

| 2013 | 17.9p/ kWh | £1,569.84 |

| 2017 | 18.5p/ kWh | £1,621.40 |

| 2020 | 22.0p/ kWh | £1,924.52 |

| 2023 | 34.0p/ kWh | £2,970.24 |

Problems can arise when prudent planning has failed to take place; this is usually at the juncture where a maturing animal moves to an adult enclosure from the juvenile one. The power requirement to heat the much large volume to the same required temperatures can be considerably more.

2.1 Heating

In adult large-constrictor enclosures, multiple heat sources may be required.

- To adequately heat the volume of air within the enclosure to the recommended levels.

- To provide a basking area or heat island large enough for the entire snake to coil and bask beneath. This will mean multiple, high power rated fittings, associated domes and guards, and thermostatic control.

- Dependent upon the length of the enclosure, there may need to be further staggered lower output heaters (or heaters on a separate thermostat) towards the cool end of the enclosure to prevent the temperature falling below recommended levels.

2.2 Lighting

Lighting large enclosures is important for the enrichment of the species kept within. A growing pool of keepers value the use of UVB radiation with snakes kept as companion animals. The issue here is that UVB radiation diminishes over distance.

Therefore, given the height specifications recommended, this could mean multiple UVB sources being required to raise the basking area to the required level. The recommended UVI range for large constrictors should range across the enclosure from 0.0 at the cool end to 1.0–2.0 at the basking area.

With the key being to drive UVB down onto the basking area, the use of high-output bulbs such as mercury vapour lamps may be beneficial as they will outperform the distances achieved by conventional UV tubes.

Full spectrum lighting, or those replicating daylight, are recommended for replicating a large constrictor’s circadian rhythm. These will certainly be needed if real plants, bushes or trees are used within the enclosure.

Enclosures should ideally have a lighting (photo) gradient much the same as the thermal gradient. This will effectively provide a bright end and a dark end in the enclosure. Lighting should be concentrated around the heat sources. UVB radiation can only be absorbed by way of heat, so thermal and photo output should not be mismatched.

2.3 Insulation

Of particular importance in ex-situ enclosures, insulation will be essential to mitigate heat loss, create an even thermal gradient and limit power consumption. Power consumption could easily become unmanageable without considerable insulation to preserve the energy.

3.0 Financial implications

During the neonate and juvenile stages of a large constrictors lifecycle, their potential costs from a spatial and energy consumption perspective remain much the same as any modest size snake. However, as these species attain lengths of 400cm within 3–7 years, spatial sacrifice and considerably increased energy consumption can be expected.

Any potential owner must consider the impact on family finances in time. At no point would it be acceptable for a potential owner to buy a large-constrictor species with the inclination to only keep it through the neonate and juvenile lifecycles. Companion animals are for life and any potential owner has a responsibility to thoroughly consider the future for their pets.

Specialist companion-animal selling businesses should put considerable emphasis on the changing requirements of large constrictors as they grow. Any potential owner bears the total responsibility of deciding if they are capable, spatially and financially, of providing for such a species long term.

4.0 Health and safety

Regardless of the taxa, any large or powerful companion animal should undergo a risk assessment to ensure the owner exercises safe maintenance and interactions with their pet. Many large constrictors become totally tame, but within the enclosure occasional territory disputes and instinctive feeding responses mean keepers should always be alert of where the snake is and read its body language.

4.1 Entering the vivarium

The vivarium or room should have viewing panels or a glass doors so the position of the snake within the enclosure can be assessed prior to entering. If it is nearing a regular feeding interval the snake may be in hunting or roaming mode and be triggered by movement within the vivarium.

4.2 Distancing tools

Snake hooks are essential when working with large constrictors. While they may not always be used to pick a snake up due to the body weight involved, they can be used to signal your presence to the snake. This practice is called tap training, and it can help the snake to realise your intention within the enclosure. Being tapped means a keeper has entered the enclosure. This practice should be undertaken from an early age for snakes to learn the significance of the taps. If a snake is becoming inquisitive and moving towards the keeper and needs to be dissuaded, a snake hook can also be used to safely guide the head away from the keeper as they work within the enclosure.

4.3 Young people

Great care should be taken with young keepers and they should not be allowed inside the snake’s enclosure where the snake is more likely to feel territorial. If a keeper wishes for a young family member to meet their large constrictor, this should be done in an open space. Under no circumstances should young children pat or pet the head of a large constrictor. Instead they should be encouraged to stroke the snake further down the body. A young family member should never be left alone with a large constrictor.

4.4 Traditional family pets

Large constrictors are predators and are often opportunistic in their feeding habits. Great care should be taken to make sure any other pets cannot come too close to a large constrictor. Fur, dander and smells from smaller pet mammals, such as rats, guinea pigs, rabbits and ferrets, may cause a feeding response from a large constrictor. If small mammals have been petted, clean clothes should be worn and hands thoroughly washed before working with a large constrictor.

4.5 Handling

Interaction with large constrictors can be hugely rewarding for the keeper while also offering enrichment for the snake. Care must be taken when moving a snake due to the sheer weight some species may attain. Some large specimens can weigh up to 90kg. There is a real risk of a keeper injuring themselves when trying to lift such a specimen alone.

Snakes should not be dragged from the enclosure and should be lifted out to avoid injury to the snake or its skin. Snakes should be handled in open space where the snake can investigate its surroundings. Avoid areas of clutter or outside areas near trees. If snakes can wedge or coil themselves around objects it can be difficult to retrieve them and return to the enclosure.

4.6 Assistance

Safe handling and removal of large constrictors from the enclosure will involve assistance from competent fellow keepers. Adult large constrictors will require a second or even third person to safely remove them from the enclosure. Does the prospective owner have such a support network in place?

5.0 Common health issues

On occasion large constrictor species can become ill. Most common ailments would be respiratory infections (pneumonias) and skin shedding problems. These are symptomatic of incorrect temperature values across the length of the enclosure, and where relative humidity levels have been allowed to drop too low. Other issues which may occur are external parasites such as snake mites. These will often be introduced by tainted substrates or decor. There are a range of treatments available to treat such infestations.

5.1 Specialist veterinary practices

Regardless of the species being sold, companion-animal selling businesses should signpost local veterinary surgeons that are proficient and comfortable with the species being sold. As part of LAIA regulation, pet-selling businesses should be registered with a local specialist veterinarian, so this vet is the obvious choice for the prospective keeper’s requirement. In the event that the prospective owner has travelled a distance to be assessed, it is the prospective owner’s responsibility to prove they have identified a suitable and local veterinary practice.

5.2 Pet insurance options

Pet insurance should be mentioned to a prospective owner and they should understand what is and is not covered. Given the mass of large-constrictor species, the volume of items such as antibiotics should they be needed would cost considerably more than regular-sized pet reptiles. It may therefore be pertinent to take out an insurance policy to help in the event of illness or injury occurring.

5.3 Microchipping

In the event of escape or theft, a microchipped large constrictors can then be traced to their owner. This will also dissuade keepers from wild releasing their animals should their circumstances change. Having an animal microchipped is relatively low cost and causes no long-term detriment for the animal. Microchipping their animal will also demonstrate a heightened level of responsibility when voluntarily undertaken by the owner.

Other considerations

Feeding

Some large constrictors will happily drop feed, which means leaving frozen-defrosted prey items to be discovered within the enclosure. Other specimens will only feed if the frozen-defrosted prey item is made to move or shake, so a method for moving the prey item is necessary. Large constrictors should never be fed by hand.

Many of the species within the scope of this document also use infrared heat pits in the face to detect their prey. A keeper’s hand will register as hotter than the prey item, and this could present a target which determines where the snake decides to strike, coil and subdue prey. This is why apparatus such as litter pickers should be used to hold frozen-defrosted prey if strike feeding is the preferred method of feeding.

Feeding intervals

Reptile obesity is a frequently-seen issue in captive reptiles, because keepers are often too generous with food. The metabolic rate of large constrictors slows into maturity, so the frequency of feeds should be reduced considerably. Large constrictors are capable of consuming huge meals which will keep mature snake satisfied for several months.

Sourcing food

Rats, guinea pigs and rabbits will eventually be too small for large constrictors as a single meal However larger prey items are not commercially available, and using multiple smaller prey items such as rabbits could become prohibitively expensive. Prospective owners may need to look at ways of sourcing larger prey items that are not commonly or commercially available.

Cohabitation

Generally, this to be avoided unless breeding trials are underway. Males of particular species can become combative and highly aggressive during the breeding season, so great care must be taken. Feeding cohabiting snakes can also be complex, creating a multitude of risks.

Two 400cm snakes fighting over a prey item is not a situation in which a companion animal owner wishes to find themselves in. For the most part, if cohabiting can be avoided then it should be, as this will make the enclosure a safer space for the keeper and the kept.

If businesses require further clarity about the assessment process, its purpose or any other issues please email Charles Thompson, Trade Delegate at: c.thompson@repta.org or contact us here.